怼duǐ : Not Your Average Conflict | China Buzz Report

(A month ago, inside a restaurant in Sanlitun, Beijing)

![]() Yan: (Sitting down while angrily pounding) Guess what? I duǐ-ed someone on Weibo just now!

Yan: (Sitting down while angrily pounding) Guess what? I duǐ-ed someone on Weibo just now!

![]() Me: What? With who?? How???

Me: What? With who?? How???

![]()

Yan: There was this “big V” (influencers and public figures with substantial followings on Weibo ) film producer who posted a picture he took inside a cinema - a photo of the big screen while the movie was still playing! Can you believe it?! I was so pissed that I duǐ-ed him by commenting, “Sir, you are not supposed to take pictures inside cinemas for copyright’s sake”, and he duǐ-ed me back just now, replying that he just wanted to “encourage more people go to the cinema and help develop the domestic movie industry”. Bullsh*t excuse!

![]() Biyi: Haha congrats on your first “互怼” (a mutual/reciprocal “duǐ” ) with a celebrity, go girl!

Biyi: Haha congrats on your first “互怼” (a mutual/reciprocal “duǐ” ) with a celebrity, go girl!

During that lunch, me and Yan spent a decent half an hour discussing cinema ethnics in China (as a devoted movie fan, there's nothing more important to Yan than a quiet and pleasant film-watching environment, and she takes those who disrupt cinematic orders very, very personally...), yet our attention was also drew on another issue: where on earth (on China, more accurately) is this duǐ verb coming from? In recent months, we've heard it everywhere in TVs, movies, social medias and on streets; the character seems to have replaced all the other conflict-related verbs in Chinese (there are a lot of them, trust me) and now triumphing as the ultimate description for confrontational situations in life. Why? Why duǐ, why now , and why in China?

To find out, we settled into cuddly positions with our laptops and clicked into Baidu Baike (basically a crappy version of Wikipedia), the unavoidable first stop for any online research in China.

After browsing two lines on the page -

“Wait a sec, I thought this character is pronounced duǐ??”

“So it’s actually duì (the forth tone) not duǐ (the third tone)?! What?!”

It turns out we've been wrong about the character's pronunciation all the way, shhhh...

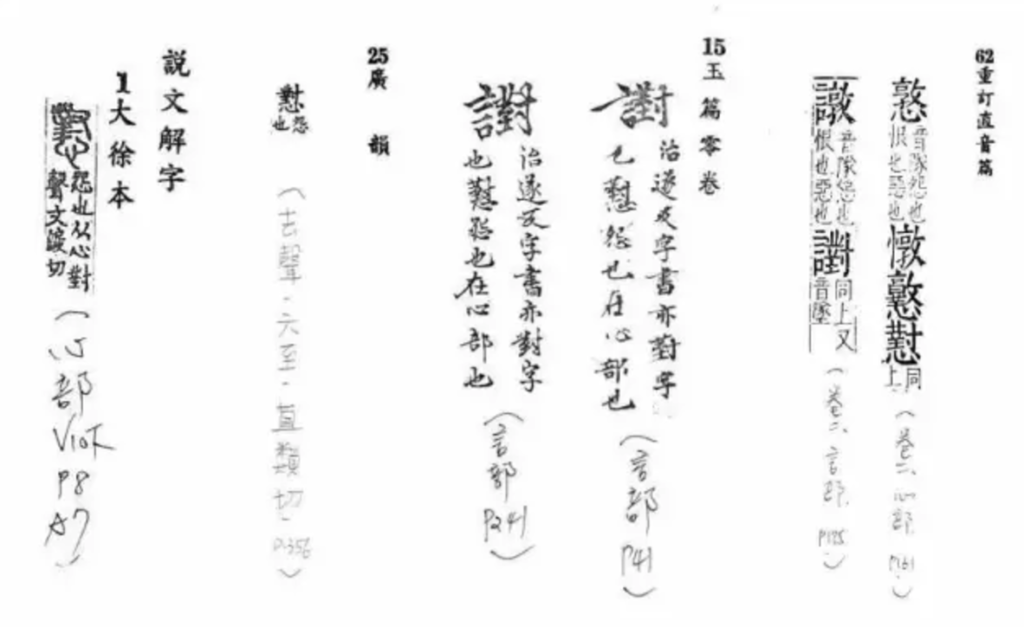

According to Baidu, the character held a long history in ancient Chinese, being used frequently by poets and writers to express one simple and strong meaning: resentment.

怼(duì) in ancient Chinese.

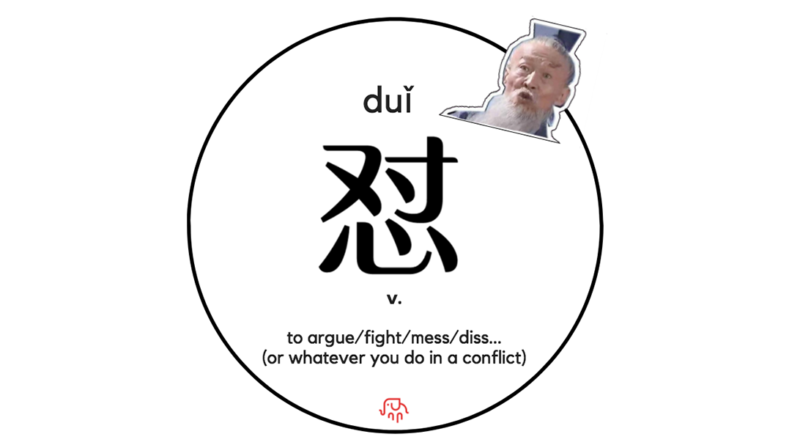

How did that handy little “怼 duì” evolved into today's “怼 duǐ”? What social and cultural changes did the character carry along with its pronunciation shift?

Take a seat, pour yourself a hot cup of Chinese tea, and let’s see where we'd end up in this investigative journey (the two of us have been watching a lot of Rap of China lately, so excuse the inept rhythmic practice here and there please...).

Regional to Internetional

First things first, let’s tackle the pronunciation shift.

A quick tour around the internet provided us with a hint: before the character went viral online, apparently it was already pronounced as duǐ in Henan, a province located in the central part of China with over 100 millions population. In fact, in Henan dialects, 怼 duǐ was widely used as a “one-fits-all”, universal verb like do or have in English; you can basically duǐ anything with anyone, at any time.

Everything sounded cool, only that the internet could lie. When I checked with my boyfriend whom the entire family is from Henan province, he told me yes, the locals do use the character to describe almost everything, but no, they pronounce it as duī rather than duǐ, another different tone (the first tone) that unlikely to have inspired today’s 怼-as-duǐ internet lingo.

If not Henan, where was duǐ's hometown then? Since neither me nor Yan speak dialects other than Mandarin, we went to our friends and families asking about how they pronounce “怼” locally (we finally figured that human beings are actually more resourceful than the internet...). The responses?

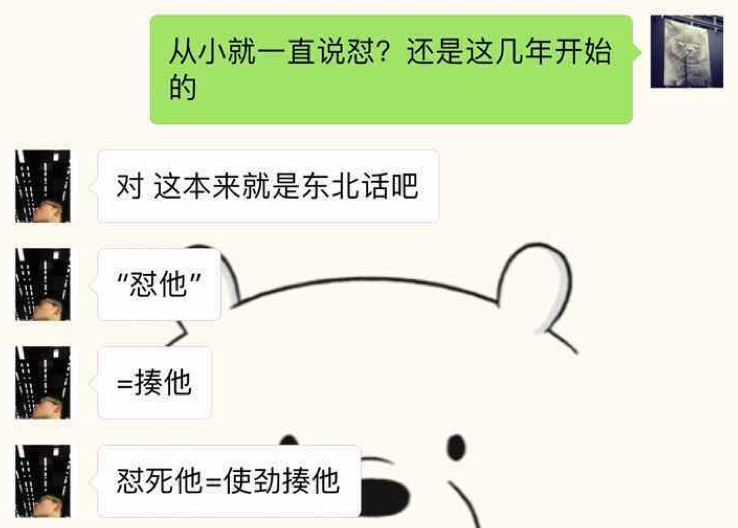

Apparently, the 怼-as-duǐ pronunciation was adopted in many Northern Chinese regions such as Dongbei, Tianjin and Beijing, and other more central provinces such as Hubei and Shandong as well (to our delight, none of our friends was aware of the character's duì pronunciation in dictionary, uh huh!).

Our Dongbei friend telling that the locals have always used “duǐ” for the meaning of beating/fighting.

One problem solved, now onto the next, more internet-relevant question: even if duǐ had been a common verb in many regional dialects, how did it go full-fetched “internetional” (yep, we made up the word) in China? How did The Chinese internet and “怼duǐ” find their ways to each other?

HongKong TV program investigating the popularity of “怼” on the Chinese internet.

Like the other internet slangs we’ve talked about , 怼duǐ was, in the very beginning, discovered and reinterpreted by Chinese netizens from domestic entertainment content.

In Summer 2015, a reality show named “Takes a Real Man” aired on Hunan Television showcasing a group of male celebrities’ being temporarily enlisted to the Chinese army. In one of the early episodes, the show featured a scene of the officer cadre rejecting one celebrity’s request to use the toilet, simultaneously lecturing on the importance of duǐ as a moral conduct. “Duǐ is a test to your soul”, said the officer to the celebrity, “no duǐ, no progress.” (We are suspecting the officer is from Dongbei given his accent…)

The officer talking about 怼 on camera.

The show was pretty well-received, yet it wasn’t until a group of newcomers - the livestream hosts - joined the Chinese internet scene that 怼duǐ eventually escalated into a more inclusive, national slang.

As you might have heard, many of the popular Chinese livestream hosts are all from the same area: Dongbei, or the Northeast provinces of China.

In China, Dongbei-ners are famous for their candid humor, wild drinking culture and sometimes, violence... (*excuse the regional stereotype here, we love our Dongbei friends!)

For those earn their livings through virtual rewards on livestream platforms, being engaged with the viewers is the most important part of the job. A good host never stays quiet; in between their mic-shouting, dancing, singing, or game-playing sessions, they'd constantly be chatting to the microphone about miscellaneous things, laying bare of many authentic local slangs that viewers from other regions might not have heard of. 怼Duǐ, a popular verb used in Dongbei dialects to express the meaning of quarrels or fights, was thus brought out to a mass online audience from the mouths of Dongbei live-streamers.

Sometimes live-streamers would "connect-mic 连麦" with each other for chats singing together for their viewers.

And such, ladies and gentlemen, was the one last push that completed the nirvana of 怼duǐ online. In less than two years’ time, the character managed to cut off from its 怼duì past, transforming from a small, regional-based communicative verb into a sweeping jargon of the Chinese Internet.

Meanings of the Meaning

What are people talking about when they talk about 怼duǐ in today's China?

As the conversation between me and Yan demonstrated, one of the most typical scenarios for using 怼duǐ is to describe conflicts, physically or verbally, online or offline. To say “I duǐ-ed someone” could imply that you had a quarrel or a fight, or somewhat a mixture of both.

I know what you might be thinking - doesn't this world already have enough verbs to describe conflicts? Seriously, in both English and Chinese, any literate person could easily pick up at least three verbs to describe the many variate forms of human conflicts that everyone encounters at different points of their lives. What makes 怼duǐ stand out from the crowd? Well, here’s our thesis:

When Chinese netizens talk about 怼duǐ, they are not just talking about having a verbal or physical fight for the sake of collision. In fact, with a greater sense of individuality and concern over public justice, Chinese citizens leveraged the anonymity of the internet to unleash emotions through a language system unique to their own understanding of the society. Ancient characters such as 怼duǐ was thus discovered and redefined; sure, being angry and delivering that infuriation is a major part of 怼duǐ, but beneath all those heated emotions lay a fundamental belief in justice, and a genuine uneasiness for individual suffering or loss.

Still confused? Let’s walk through two examples of how duǐ bustled around on the Chinese internet.

- Duǐ to parents and relatives (怼父母/怼亲戚) :

Over the past two years or so, China's young ones have been increasingly vocal online about one rather personal subject: the discontent they hold towards their parents and relatives. We all know that family expectation is a huge, life-long pressure for many Chinese, yet the idea of filial piety (Xiào孝) is so deeply embedded in the Confucius culture that complaining about parents or relatives, especially the elderlies, was considered an abhorrent moral corruption in the past. Thanks to the rise of social medias however, nowadays more people are open to share their family stories publicly, exchanging tips and ideas on how to fight for individual freedom as young, independent adults.

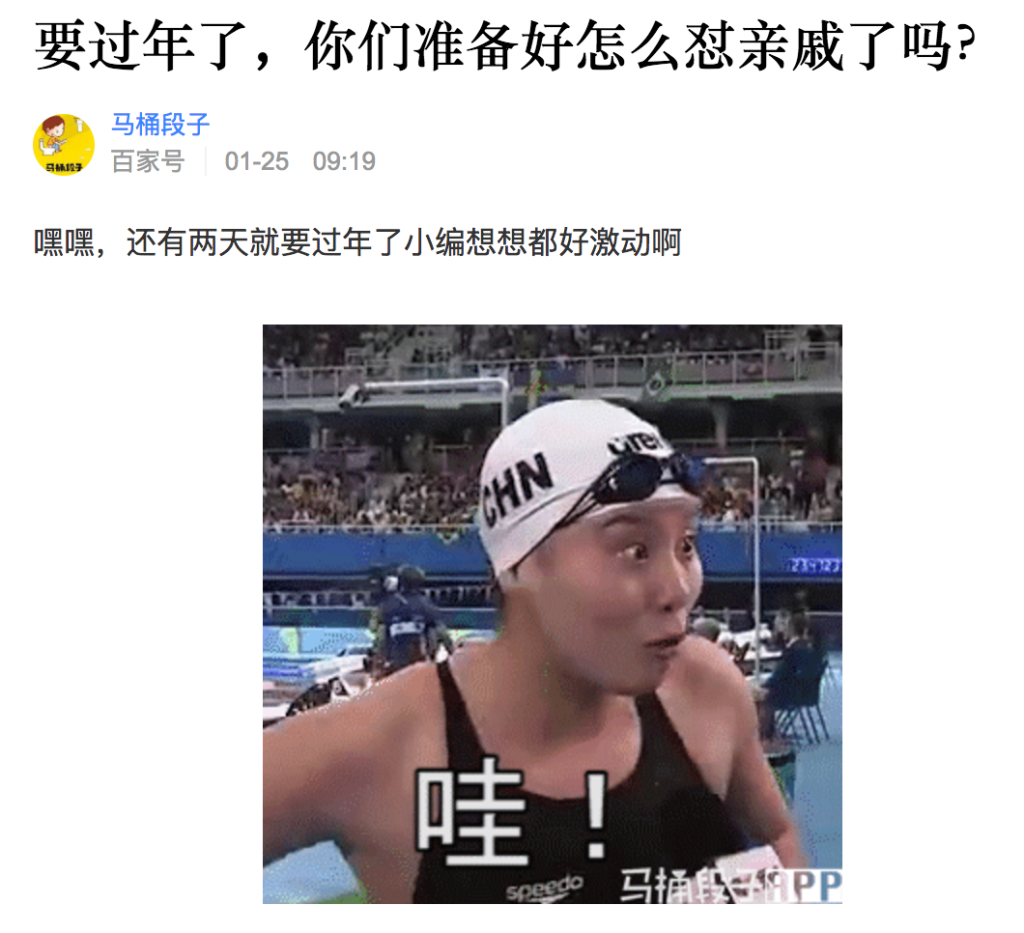

An article titled "It's Spring Festival again, are you ready to 怼duǐ your relatives back home?"

“How to duǐ parents and relatives” indeed has become a trending topic on social platforms where young people congregates; so much that the Chinese government had to shut down an “anti-parents” forum on douban.com this year for its “negative influence on the society” (the forum had over 100,000 active members before being shut down).

The "anti-parents"group that was shut down early this year. (As extreme as the group name sounds, it indeed acted as a helpful mentor for many suffering from family pressures and troubled relationships with parents. )

- Duǐ GMO(怒怼转基因):

Another topic that attracted a lot of “public duǐ 互怼” over the past few years is GMO (genetically modified crops).

In 2013, former TV host and producer Cui Yongyuan filmed an investigative documentary questioning the safety of GMOs through a two-week journey to the United States. The documentary was widely viewed and quickly criticized by various scientists, scholars and concerned netizens for its lack of objectivity, yet Cui persisted fiercely with his anti-GMO campaign to conduct further private investigations while wrangling with skeptics online. Their back-and-forth debates soon escalated to a major duǐ event on Weibo; almost four years in, those in support of GMO food and fans of Cui are still in a flamed war-of-words, frizzling over issues from the science of GMO to Cui’s mental health.

Cui is basically now the king of duǐ on Weibo.

Cui and GMO, in this context, is a symbolic representation of public debates in today’s Chinese internet: the immense amount of 怼duǐ might look like pure emotional rants from the outside, but a closer study of their arguments will reveal the ardent, socially-conscious Chinese netizens' bursting desire to talk and to participate in public affairs.

Duǐ, Trump, and the Hip-hop Diss

Having talked quite a bit about 怼duǐ’s unique birth in the Chinese language and today’s domestic internet culture, we want to wrap up this week's discussion by positioning 怼duǐ in relation to two more international/less “Chinese” phenomenon: president Trump and the “diss” culture in Hip-hop.

President Donald Trump might not be the biggest fan of China, but ironically, according to Chinese media, he’d definitively nailed the tricks of 怼duǐ even better than average Chinese citizens. In fact, Trump himself has been incredibly helpful in both inventing and incepting the meaning of 怼 duǐ to everyone that follows Chinese news; still confused about the meaning of duǐ or how to use it in everyday conversations? Just check out these headlines talking about Trump's relentless 怼 duǐ with, you know, everyone:

"Trump 怼 duǐ China", ""Trump 怼 duǐ Meryl Streep", "Trump 怼 duǐ media"...you get the idea.

Last but not least, D-I-S-S.

This summer, as the reality show Rap of China went viral (the show's first episode received over 100 million views within 4 hours), Chinese fans began to take notice of the “diss” culture in Hip-hop music: primarily intended to disrespect a person or group, “disses”, or “battle raps” have been established as a key part of the Hip-hop scene since its inception.

Rap of China is the hottest show in town at the moment.

Young Chinese who just kindled their love with Hip-hop might not know about the cultural or historical backgrounds of diss (we are talking about ourselves, aka two hot-headed fans who’ve been obsessively following the show every week), but that didn't stop them to assimilate “diss” into everyday conversations as soon as discovering it in the show. Many creative netizens have even started to write their own diss songs, using it as an expressive outlet to talk about domestic news and private affairs all with a touch of Hip-hop.

Chinese rap group Higher Brother's song "made in China" was a real hit this year both in China and the western world.

So what about the future? Will “diss” overtop “duǐ” in narrating conflictual scenarios in China, or will it develop into an even bolder, more aggressive discourse in the mouths and fingertips of today’s young Chinese? We'll save these questions for now (honestly, we really just have A LOT OF questions), keep our radar open while hustling in town, and get back to you for another week's Elephant discussion.

A meme for those who had watched Rap of China - you get it...

对對 the top part has the basic meaning of “correct” It is more than a phonetic here. It is composed of 寸 cùn (hand or measure) and 丵 zhuó (a hedge) and 土 tǔ. ( earth). Its original meaning was to create a “correct boundary” and keep “proper relations” as in 相對. So one of its basic meanings was “boundary” . So 懟 means a “boundary” 對 of the 心 “heart”, or “hate”. Uncle Hanzi in Huangshan 2017