#MeToo in China: the Story Beyond Censorship

On January 1st, 2018, Luo Xixi, a graduate of Beihang University, posted an open letter alleging her then adviser Professor Chen Xiaowu for sexual harassment. The professor, Luo recalls, asked her to come to his house to tend houseplants, and tried to have sex with her despite Luo’s crying plead. Professor Chen eventually stopped when Luo told him she was still a virgin, “I was just trying to test your moral conduct.” Chen defensed himself, and threatened Luo to not mention what happened to anyone else.

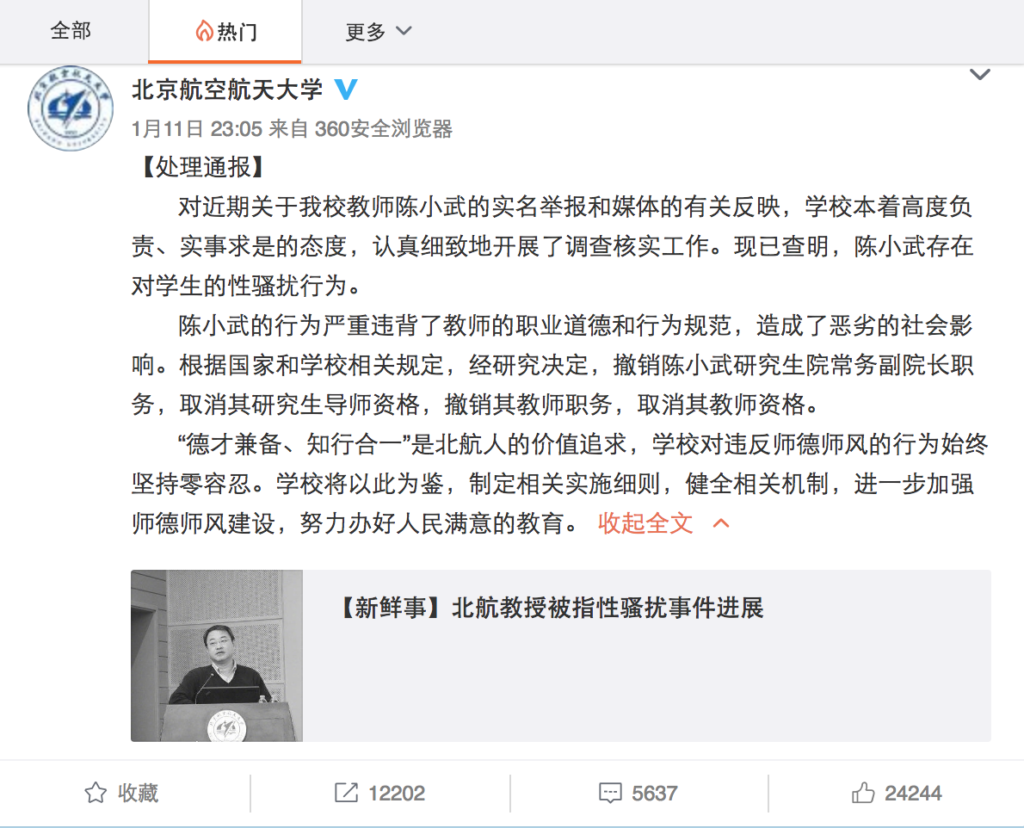

Within a day, Luo’s open letter received three million hits on Weibo. Encouraged by public support, Luo posted another letter on Jan 5th, revealing further details of Professor Chen’s sexual harassments on other female students. The next day, The People’s Daily, an official newspaper of the CCP, addressed the issue on Weibo in praise of Luo and the other victims' courage, and called for quicker, better legislations on the matter of anti-sexual harassment. On Jan 11th, Beihang university publicly announced that the school had decided to revoke Chen’s position as a graduate tutor and to cancel his teaching qualifications. Four days later, on Jan 14th, the Ministry of Education spoke about the case to media, saying that the government would continue to hold a “zero-tolerance “attitude to any ethical violations, and that the Ministry will begin to establish long-term mechanism for harassment preventions in colleges and universities as soon as possible.

Beihang University's determined and transparent response received wide applause from the public.

“We were really amazed by the University and the Ministry of Education’s response,” says Qiqi Xiao, a current sociology major in the University of British Columbia and an active campaigner for women’s rights in China. “I was actually in the process of organizing an online petition addressed to the Ministry of Education, yet before we finished, they already responded. In the past, incidents like this - even after being exposed - would often go unanswered. This time though, we feel things are different.”

It certainly did, at least according to Qiqi and her activist peers who have embraced the feminism agenda and are now opening pushing for changes in China. Immediately after the Ministry’s announcement, more Chinese institutions publicly denounced sexual harassments, establishing study groups, in-school clinics and revising revise school polices over the subject matter.

Among those who came out the quickest and strongest, most were not elite universities, but small institutions from sometimes even remote locations. “The outsiders might only care about what Tsinghua or Peking University did,” says Qiqi, “but for us who are actually running the campaign, we are thrilled to see so many less well-known schools standing out. The grassroots nature of our movement deserves more credit.”

The Mysterious Life of a Hashtag

Supports from the government didn't just happen automatically. Behind such progress from the top lies an internet movement created by the people, and carried by the mass.

Qiqi created the #metoo在中国# (metooinChina) hashtag two days after Luo Xixi’s open letter on Weibo. Ever since witnessing the MeToo movement gaining momentum in North America last year, she’s been thinking about how to borrow its influence and localize the campaign in China. Now, it seemed to be the right time.

The hashtag experienced a rather mysterious life journey on the Chinese interenet. When Qiqi first started, she used #Metoo在中国# with a capital M; after submitting a few posts and applying for the topic/hashtag host on Weibo, she noticed it was automatically changed into #metoo在中国# with “m” now in lower case. “From what I know, Weibo doesn’t differentiate upper and lower case letters in hashtags, so I had no idea why it got changed.” Qiqi recalls.

In 13 days, the hashtag “#metoo在中国# received over 4,000,000 views and 4,171 comments, and even made its way to the top of Weibo’s trending charity hashtag chart. Then, on Jan 17th, it disappeared. Clicking into the hashtag, all it would show is a cold notification saying “sorry, you’ve entered the wrong address”.

But that wasn’t the end of the story. When #metoo在中国# died, #Metoo在中国#, the upper-case version that originally created by Qiqi on Jan 3rd, was being put back to live. The hashtag has survived until this day, accumulating over 5,000,000 views and 5,760 comments.

Left: #metoo在中国#, now unavailable; Right: #Metoo在中国#, still alive.

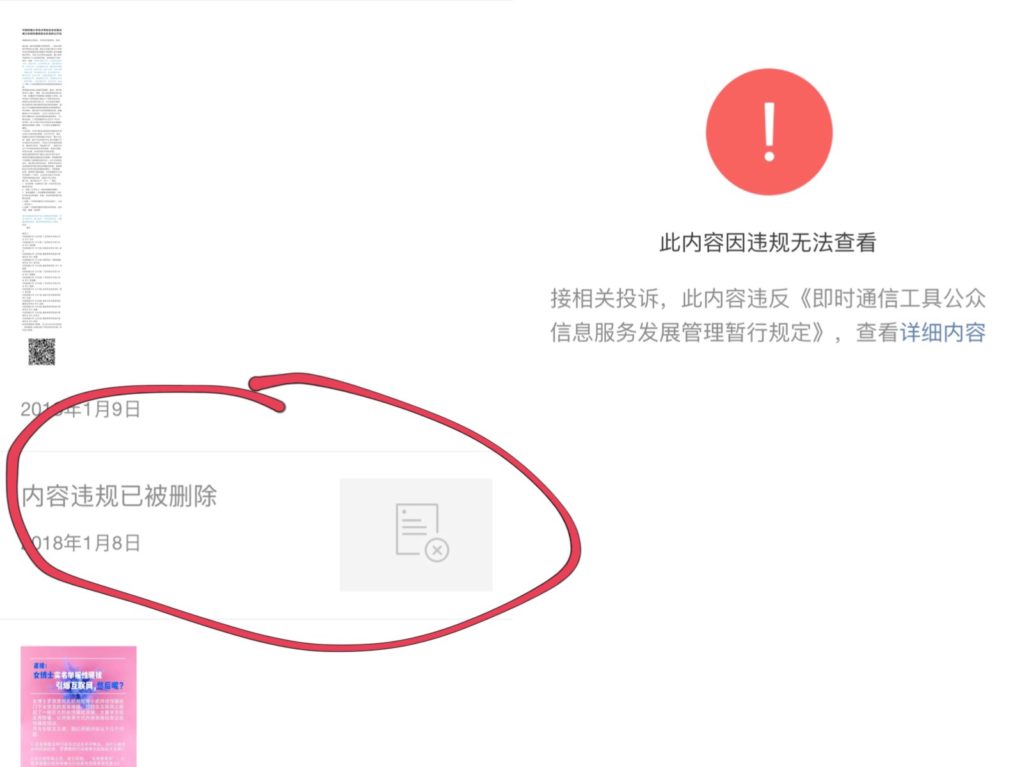

Other campaigns certainly haven’t been so lucky; many articles with “sexual harassment 性骚扰” in the titles got deleted, and some were not able to submit their posts on WeChat if they contained sensitive terms such as “petition” (联署) or “real name” (实名).

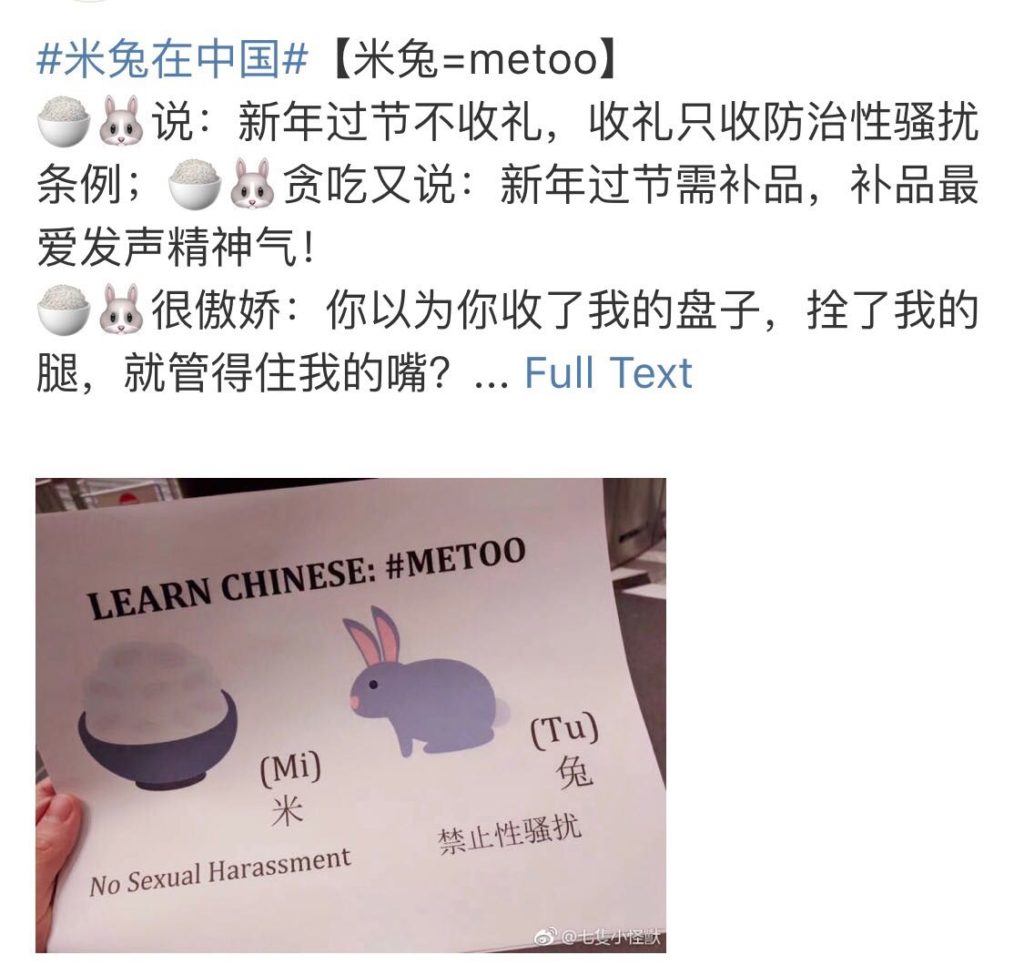

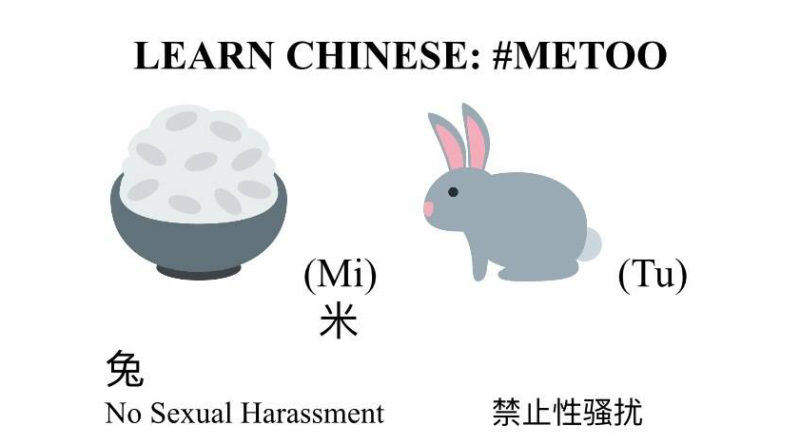

Censorships on WeChat (From the WeChat Public Account of Meili Xiao, another active campaigner for #metoo and feminism.)

But like the old Communist saying goes, “上有政策, 下有对策” (those on top have policies, those on the ground have solutions). When censorship came, Qiqi and her activist friends found ways to circumvent through: they quickly created new terms and slangs to replace the sensitive words, for instance, translating “metoo” into “米兔” (rice bunny) accompanied with cute emojis. To navigate through text filters, they made sure all of their articles were posted only as screenshots in photo format. Finally, if a piece of public content was still deleted, they’d use private channels instead, circulating them through emails or personal chats.

From "metoo" to "Mi Tu".

“Censorships? Of course,” Qiqi laughs, “but so? By now we all know that’s inevitable for any social movement in China. For us, censorship is part of progress, not the end of the story.”

The Merit of Not Against

Last week, my friend Ceci, a current PHD student at University of Toronto and an active feminist, began to organize an online petition from oversea Chinese students. Addressing directly to the People’s Congress, the petition calls for government action in anti-sexual harassment legislations both in and beyond the academia.

When Ceci contacted one of the most prominent, government-owned Chinese media asking for support, she got a rather ambivalent reply. “We are with you on the agenda and would love to share your petition,” says the editor, “the thing is, sexual harassment is not hot on the news at the moment. So even if we shared your letter, honestly, if wouldn’t receive many clicks.”

The editor’s attitude, while on one hand could be easily judged as "unethical" according to western journalist standard, wasn’t a sign of total negativity for Ceci and her peers. "The medias are still allowed by the government to talk about sexual harassment, that’s already a good news!" Ceci says cheeringly.

Although government media turned it down, the petition was circulated through WeChat public accounts and other Chinese internet media.

When Qiqi contacted Sichuan University, her previous school and one of the top universities in China for support, the feedback she got experienced a nuanced shift. In the beginning, none of the teachers said anything back. The next day after the Ministry of Education’s announcement however, she received a message. “Hope you understand, us inside the system (在体制内) are difficult to speak openly on sensitive issues like this. But we’ve been following your campaign online and are proud of what you’ve done.” The professor encouraged her.

Not against it, but not in public support quite yet - such seems to be the attitude that most people hold towards a movement like #MeToo in today's China. It’s not a bad one, after all.

“Perhaps we are being over optimistic, or perhaps we are just evaluating our progress based on the historical context of social movements in China,” says Ceci. “either way, there’s no reason to lose hope just yet, don't you think so?”

-

About a month ago, we’ve started to receive questions from readers regarding #MeToo in China: “So, what's going on? ”

On our journey to figure it out, we first encountered reports from English media outlets such as New York Times, New Yorker, Reuters and NPR. Yan and I were fascinated by the investigative details they provide, at the same time, we found ourselves to be almost angry by the fact that all of them framed censorship as the crux of the story. There's no denial that censorship is an intrinsic part of an authoritarian regime at a collective level, but surely there are more?

Anti-sexual harassment still has a long, long way to go in China. This is a country that still lacks effective legislations and public supervision mechanisms, still self-conflicts ideologically in between the Maoist notion of “women holds half of the sky” and an extremely patriarchal social traditions, and still missing cultural tolerance for victims to stand up and tell their stories with courage. We are not turning an blind eye to these problems, but we feel it is also important to recognize that changes are happening even just in very subtle and reserved ways. The awareness #MeToo has yielded in China may be insignificant compared with the mass movement going on abroad, but it so far has been a cheerful start, and those who participated are not going to give up just yet.

“There are a lot of obstacles and we might be seen as handcuffed, ” says Qiqi before we wrapped up our conversation, “but who says one can't dance with handcuffs on?”

![]()

It is now almost Chinese New Year by the time you see this article. So first, a big shout out of “HAPPY NEW YEAR 新年快乐” from us to you, no matter where you are and how are you celebrating it 🙂

Secondly, the oversea Chinese students petition for anti-sexual harassment is still going on. We encourage you to click here to participate, or forward the petition to oversea Chinese students of your knowledge.

Sex and gender in China is perhaps the topic that Yan and I are the most curious about, and we will for sure delve wider and deeper into it this year at Elephant Room. Let us know if you have specific story suggestions, or want to join our journey of exploration in any other way by leaving a comment down below, or write to us at contact@elephant-room.com. We believe changes start with conversations, don’t you?

Thank you very much and see you in the Year of Dog,

xxxx,

Yan and Biyi

What you won’t hear about, but is also very prevalent, is the male-on-male sexual abuse in China.

Your courage, persistence and positive attitude are inspiring. It is hard for some of us to get past our visceral hatred for censorship,

(especially since I had to work for a long time even to get this comment past the great wall) but most of us also know that it is the committed, steady and creative approach that yields the best results in the end. Congratulations on the

progress you and the movement have already made, and best of dog year luck to you in the future!

Your efforts are touching. It looks very normal for most of college teachers to refuse to publicly support your movement. They might be moral, but their morality is often shaded by the formal system. In China, there are almost no independent scholars and teachers because they have to make living inside the system.

An excellent report on the subtleties of MeTooChina. Thank you both and hope to know more, especially if the movement is having any impact on women’s daily lives.

[…] The great firewall of China also censored the term “#MeToo.” I suppose there have to be many sexual abusers in China who really feel they want broad safety from criticism. The emojis for bunnies and rice, and the time period “#RiceBunny” are censored as a result of “rice, bunny” (米兔) is pronounced “mi tu” in Chinese. […]

Good job, ladies! 陈愉Joy