“Rap music? China?

What are you even saying?

Is this Chinese rap music?

Sounds like they're just saying ching chang chong”

-Higher Brothers, “Made in China”

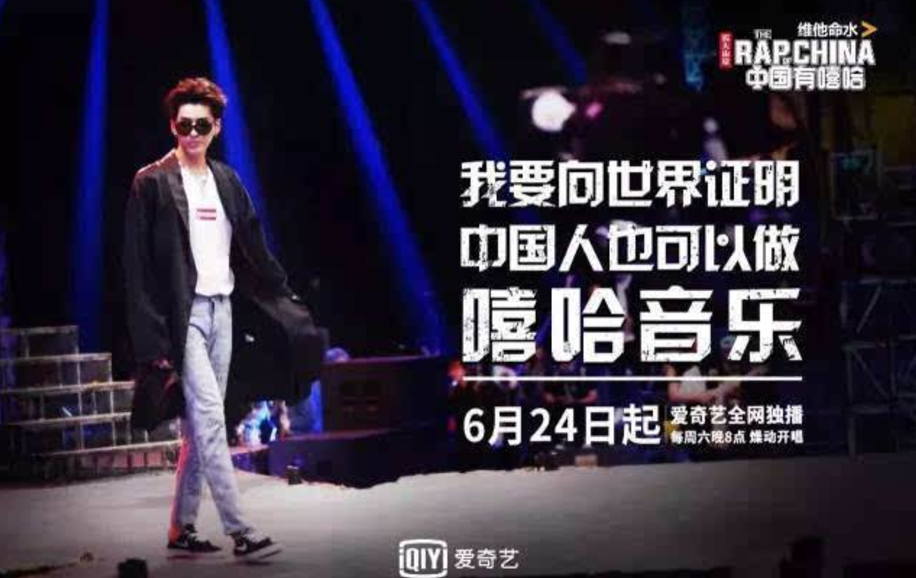

Many people consider 2017 a vintage year for Chinese Hip Hop music: domestically, the ongoing TV Show “Rap of China” has become a national entertainment phenomenon, receiving over a hundred million of views every week. Internationally, the Chengdu rap crew Higher Brothers was signed by US record Label CMG, and their singles such as Made in China, WeChat and Black Cab have all racked up millions of hits on YouTube. Within just a few months, “China” and “Hip Hop”, the two once irrelevant terms have clashed with each other in the public eyes, unleashing energetic momentums in many astonishing ways.

As a long-time Hip Hop fan who's been following the global industry for over a decade, I knew such change didn't happen overnight. Contrarily, the Chinese Hip Hop boom today is the result of a long identity-hunting journey for domestic rappers; having spend years learning and mimicking what happened in the West, many of them have eventually developed strong individual awareness and cultural confidence, and are now able to reflect them in their music through brutally honest yet also extremely powerful self-expressions.

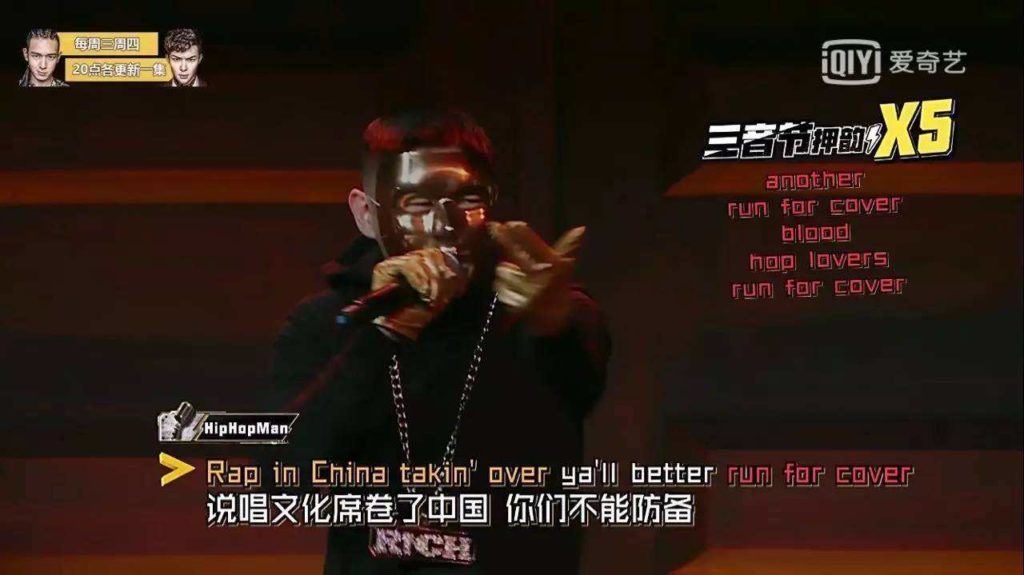

MC Jin, aka HipHopMan, joined Rap of China as a competitor after years of music career in the U.S as a Chinese-American.

From Jay Chou to Eminem

When I was 12, 13 and about to enter middle school, every classmate of mine – literally everyone - was listening to Jay Chou. During the era where all the Chinese pop songs were about falling in loves and break-ups, Jay Chou’s rap (or mumble, to a lot of Chinese parents) about Chinese Kung Fu was like a breath of crispy air into our daunting, high-pressured school life. I had no idea what Hip Hop was back then, but Jay Chou’s music was so cool that I begged my parents to get me a Walkman so I could play it all day.

Jay Chou's "Nunchucks 双截棍" was a generational memory for us post-90s Chinese kids.

With Jay Chou's murmured rap finally hugging my ears (thanks for that Walkman, mom and dad!), I bumped into streetball, a Hip Hop version of regular basketball that was gaining popularity in China. As a young, hot-blooded teen desperately looking for outlets to release energies, I immediately fell in love with this urban sport and began to play in various courts in Nanjing, the city I lived until college. Back then, a player nicknamed Rabbit was the celebrity in our circle; having had the opportunities to play with him for several times, I began to chat personally with him and learned about his passion for Hip Hop music. Rabbit recommended me to check out a few online forums where he and other Chinese Hip Hop fans were posting self-made music videos to, and from there I discovered a bunch of songs from Dr. Dre’s Next Episode to Chingy’s Right Thurr. My walkman wasn't just filled with Jay Chou anymore, instead, I developed a strong interest in American rappers, bringing along their beats to the basketball courts with me everyday after school.

People playing streetball in NYC.

And then I discovered Eminem, who pulled the last string to make me madly in love with Hip Hop. I still remember the first time I listened to his songs: reading through the lyrics line by line with an English-Chinese dictionary in hand for immediate translational help, I got goosebumps everywhere while blood pressure piped up. Never in my entire life had I heard anything so powerful; those words, those beats and the way he spat those verses, together they were like adding fuel to the fire, igniting the many dark, sleepless nights of my life. I’d watch 8 Mile, and listen to Lose Yourself, Till I Collapse, Mocking Bird, The Way I Am, When I’m Gone over and over again; I was hooked to his songs, his way of love and hate, and more importantly, his hardcore, unbeatable attitude towards sufferings in life.

Eminem in 8 Mile.

For Chinese kids growing up in the early 2000s, music was the outlet for us to establish individual identities and to find our crowds. The majority of my classmates were busy following Taiwanese and Hong Kong pop stars such as Jay Chou and Leehom Wang; yet there were also others who loved Rock n' Roll, and those who were obsessed with Hip Hop like I was. Unfortunately, unlike Rocks which already had a rather flourishing domestic scene in China in the early 90s, Hip Hop was a completely westernized notion with little domestic productions in the 2000s.

Chongqing Rapper Gai.

Made in China

To establish a confident tone in Hip Hop, an imported culture from the West, Chinese rappers began to experiment ways to reflect upon their national identities and inject their original understanding of Chinese culture into their music. One of the recent examples is Higher Brother's viral song Made in China: by openly depicting the Western stereotype on “Made in China” products, cultures and of course, Chinese Hip Hop, Higher Brothers not only bragged about China's material power, but more importantly, enacted a fresh, confident image as a new generation of Chinese artists who are proud to rap about their national identities to the world.

Higher Brother's Made in China.

Higher Brother's Made in China.

Way before Higher Brothers tried to show people around the world what today’s China is like, Chinese Americans, such as MC Jin, have sowed seeds of Chinese Hip Hop (in a broader definition) that stemmed from his urge to constantly challenge the status quo almost 20 years ago. In fact, MC Jin also mentioned the concept of “made in China” 12 years ago during a battle, “You wanna say I’m Chinese? here's a reminda/ check your Tims (refers to Timberland Boots), they probably say ‘made in china’.”

MC Jin, aka the mysterious "HipHopMan".

Another rapper Al Rocco, who is also an “Asian international” as he lived in Shanghai, Hong Kong, London and LA growing up, made an impact on Chinese Hip Hop this year as well. Self-identified as “ Chinaman”, he’s got a very unique voice that's perfect for Trap music, and his label Red8, whose name represents China’s favorite color and number, provides world-class producers to support his international music career.

Domestically, underground rappers also began to establish their identity through rapping out the many unique elements of their Chinese life - the hotpot, the traffic jam, the Jianghu, the monkey king, and sometimes, the unbearable pressure of being Chinese adults.

Beijing crew “Yinsaner” (阴三儿), three Chinese Hip Hop veterans to whom I had nothing but respect, were among the first to rap about down-to-the-ground Chinese life. The first time I heard their music was 5 years after they released their most popular work – Hello, Teacher (老师你好), and it completely cracked me up in the library. What they rapped about was exactly what I experienced in the Chinese classrooms; the song was so real, full of authentic energy, and brutal with a humorous twist.

(The Hip Hop trio recently became the victim of the Chinese censorship though: banned due to “obscenity, violence or crime” and said to have “harmed social morality”, the majority of their songs are now removed from Chinese music streaming platforms.)

Yinsaner's Beijing-style rap is rustic, brutal, yet also with a twist of humor.

Chengdu rapper Shady's (谢帝) song Daddy Ain't Going to Work Tomorrow (老子明天不上班) was a massive internet adoration when it came out in 2013. Rapping in his distinctive Chengdu dialect, this song by Shady was a direct cry-out for China's highly-pressured working class.

Chengdu rapper Shady.

In China, Chengdu/Chongqing (川渝) rappers are undoubtedly the pioneers in constructing a distinctive regional identity through local dialects, at least in Hip-Hop's Trap sub-genre. A few months ago, Vice/Noisey produced a 2-part documentary called “Trap in Southwest” (川渝陷阱), which revealed a chaotic yet flourishing underground rap world after interviewing some of the most influential rappers in the region, such as Higher Brothers, Ty., Wudu Montana, Gai, and Bridge.

Chengdu Rap House currently one of the most successful Hip Hop labels in China.

Vice/Noisey's 2-part documentary featuring Chengdu and Chongqing Rappers.

Historical city Xi’an also raised an extremely competitive label “Triple H” (红花会), featuring rappers like MC BeiBei, AKA “贝爷” known for his freestyle battle skills, and PG One, who is debatably the No. 1 seed in the Rap of China show thus far. Their music possesses strong sense of Xi'an identity with a focus on rhythmic freestyle flows.

Triple H performing live.

Looking Forward

As underground rappers emerged to the public entertainment scene thanks to Rap of China, many observers also began to wonder about the future of Chinese Hip Hop: as some of you might know, rap originally stems from a culture that has been seeped in the fight against political, social, and economic oppression; violence, rebellion and sexually explicit lyrics are common themes that run through some of the top rappers' works ever since the genre was coined in 1970s.

Speaking up for public issues is the fundamental spirit of Hip-Hop; yet it is also what the Chinese government fears the most in today's political climate. With much scrutinization and censorship already being conducted, can Chinese rappers stay true to their hearts while continue to make genuine, powerful beats as some of them have attempted in the past?

With as much worrisome as you probably hold, I do, in the end of the day, possess a leap of faith in the future of China's Hip-Hop. In fact, having personally witnessed many Chinese rappers struggle, survive and grow in a rapidly changing ecosystem, I am nothing but appreciative of the public celebration of Hip-Hop today. Let the Chinese Hip Hop spread more awareness first, and with more pioneering rappers discovering their true identities in music, it would not matter Trap or Old-School, censorship or not, as long as the beats and rhythms accurately reflect what they truly represent, then we will be able to proudly say it out loud, “China has Hip Hop (中国有嘻哈)”.

A Rap of China poster with the slogan "I want to prove to the world that Chinese can also make Hip Hop".

Bo is a Nanjing boy who studied in the US, and currently in the hedge fund industry. He hold BS in Finance from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

[…] This article offers a great overview of Chinese hip hop, with links to other songs if you’re interested. The point it ends on though, that hip hop’s tradition of being part of counter culture, criticizing authority and being a bit vulgar when the mood suits it don’t really mesh well with the Chinese government’s views of a “harmonious society” and proclivity to censor willy-nilly (as some of the groups in the article have been). So that creates an interesting implications for this song below, sponsored by the Communist Youth League. It’s honestly good music, got flow, and considering the group’s… Read more »