Have you tried Chinese chives?

Officially known as Allium tuberosum, Chinese chives, or garlic chives/Asian chives is a species of onion native to southwestern parts of the Chinese province Shanxi. They have strappy flat leaves and grow in clumps; with a robust flavor and outstanding nutrition profile, the herb is widely used for a lot of Chinese dishes, from egg scrambles, stir-fries to buns and dumplings.

Chives dumpling - a favorite of Northern Chinese.

When it comes to planting, Chinese chives are total easy-breezy. They are fast-growing, drought-tolerant, and extremely vital; even after a long freeze, the plant will die only to return again come springtime. Thanks to nutrients stored inside the stem, after the top leafs are being cut away, the plant will keep growing and blooming into the next harvest.

“Chives could be harvested for about 10 times every year.”

In 2018, the Chinese people have come to learn one fact: we are all, in essence, chives.

"How to be a proper chive" - memes created by Chinese netizen.

The Speculators

The Chinese public first used the terms “chives “and “chive-harvesting” a couple of years ago, nicknaming the victims who were trapped in the loop of speculative investments.

-

Chives Field No.1: Blockchain

In 2017, the skyrocketing value of bitcoin made many jumped on the bandwagon of cryptocurrency. With legends of people turning into millionaire or even billionaire flowing around, everyone, including us, had considered about earning a share in the impetuous market. Chives-harvesters quickly saw the possibility of exploitation; hundreds of blockchain-based projects began to fundraise, promising to deliver revolutionary changes to almost every single industry out there in China.

A complicated technology that few could understand, a bunch of projects backed by famous investors and tycoons, and a ton of eager individuals who wished to rise to wealth with one shot - with all these preconditions ticked, “Biquan 币圈”, the “coin circle”, became the cradle-land of chive-harvesting. Regardless of government restrictions and warnings, blockchain investment went completely wild in China; in the first half of 2017, there were over 65 cases of ICOs, with the total financing scale up to 2.6 billion RMB.

Chinese articles about chives-harvesting in the "coin circle".

In July 2018, a leaked audio recording of China’s “bitcoin godfather”, Li Xiaolai, ripped the emperor’s new cloth. During the 50-minute private recording, Li went brutally honest about the industry, trashing many domestic blockchain projects as “air coins”. “The biggest value of these cryptocurrencies is consensus. What is consensus? It basically means the project itself is worth nothing, but when so many people have bought it, it becomes valuable.” Said Li during the recording.

The audio went viral on the internet. Everything Mr. Li said was unspoken knowledge within the industry, for the individuals who were lured to believe that blockchain was a gold mine though, his words were a loud face-palm. Investors and media were finally awakened to the reality: the much-hyped technology might be gloriously promising in nature, in practice however, it merely became a cover for manipulations, fraud and losses. Before realizing so, those who went into the game were already being harvested, and those who had harvested a fair share, like Mr. Li Xiaolai, were sharpening their sickle for the future yield.

"Chives, born to be harvested"

The stories of “harvested chives” in the blockchain industry caused only mild empathy among the Chinese publics. After all, to be harvested in the coin circle was in some ways a privilege already, since only those with enough capital and connections could participate in such a wild game.

-

Chives Field No.2: Online P2P-lending

For those who considered blockchain as too complicated or too risky, they were presented with another investment option that were packaged as safer, more promising, and more stable return: P2P (peer-to-peer) lending.

Over the past two years, online P2P in China experienced a dramatic rise and fall. In 2017, China stood as one of the largest P2P market in the world, in terms of both number of platforms and amount of transactions. Yet within merely 6 months this year, over 700 P2P platforms have collapsed, or as the Chinese media put it, exploded (暴雷). According to Home of Online Loaning, the affected transactions could be over 77 billion RMB.

The Chinese investors, or, as they self-acknowledge themselves to be today, the chives, were attracted to P2P at first for good reasons, some of the firms offered tempting high rate of return, some were backed by legit official financial institutions. “As my daughter grow older, we were thinking about changing to a bigger house”, our friend Tong said, “back then P2P investment was the only way of earning more income apart from my solid paycheck, so after some careful study, I chose a platform that claimed to be certified by a prominent national bank.”

In the beginning of June, the P2P platform that Tong invested in suddenly froze. Like the other platforms that “exploded” this year, there were no explanations and no compensations provided. Tong, reminded by her close friends, withdrew her money back from the platform before it went down; yet many of her fellow investors haven’t been so lucky. “In the investors’ WeChat group which I am still in, people are trying everything they can to get their money back.” Tong said, “many went directly to the police, but there was no response. No hope to get their life-savings back at all.”

What made the P2P victims even more despair is the government’s action towards the issue. Instead of urging the collapsed firms to put up withdrawing policy, the authority has been busy repressing the victims to ensure social stability. On August 6th, a bunch of P2P-lending victims went to Beijing’s Financial Street - where all the national financial institutions and regulatory agencies are located – for a planned protest. The authorities immediately took action by putting up polices forces; on some video clips circulated on WeChat, we could see dozens of police dragging protestors onto a bus, forcing them to leave the site. The repressions quickly grew in momentum as any registered P2P victims would be prevented from traveling to Beijing, regardless their purpose.

When typing "Financial Street" on Weibo, the related keywords are P2P, police, petition etc., but all the real-time news about the protest is completely censored.

The Chives State and its People

Over the past few months, the term “chives” was elevated to a new level. Today, the Chinese people are not only acknowledging themselves as chives, but also mocking the nation as a “Chives State 韭州” . It looks like we’ve finally come to accept the fact: in a country where legislation lacks transparency and power over-concentrated, every Chinese citizen is a root of Chives in the end of the day.

In the early few months of 2018, “being harvested as chives” was still just an idiom used within the finance circle. We heard our friends talking about it, saw it in news headlines and social media discussions, and, to be completely honest, disregarded the chives who claimed to have been “harvested”: acts of short-term speculations come with high risk, they should have known! There are reasons that they are the ones got harvested, of course there are!

We thought we were the superior ones. As long as we keep making wise, conservative investment choices (or just make no investment at all - so much easier!), we will never end up in that chives field and risk being harvested one day. We are safe! we are clean!

How naïve we were.

-

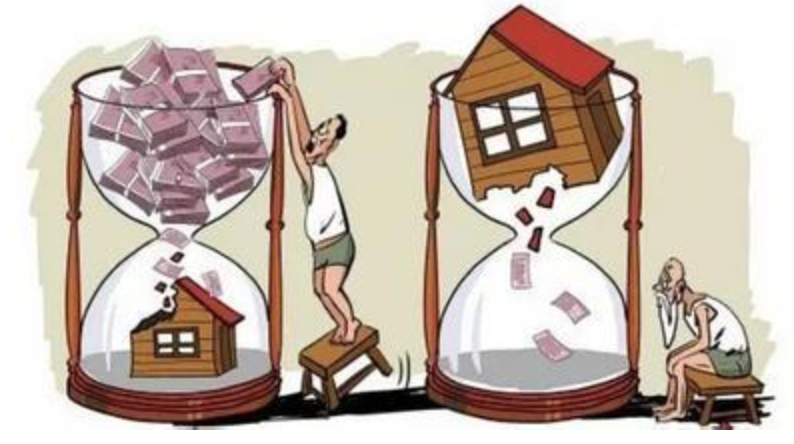

Chives Field No.3: the Housing Market

House is the most important thing in Chinese peoples’ lives. Culturally, house ownership has long been perceived as a prerequisite for marriage; most Chinese parents, especially those from the males’ side, would exhaust their entire life-saving for a new house for their sons (thus to secure the bride’s hands). Economically, despite long-running speculations about the domestic property bubble, real estate was still considered the best, and perhaps only investment tool for beating inflation. Hence everyone with money would buy a house; and those without money would do everything they can to borrow every possible RMB, and to buy a house.

At least this was how it was like for the entire past decade. From 2005 to 2016, China’s house price surged by over 66%, growing nearly twice as fast as national income. For many, the plunging property price in China was the sign of the country’s economic miracle; when everything was looking so new and so shiny, no one had time to think about its inner contradictions. Everyone just wanted to be part of the game.

While the publics imperatively wooed into the real estate market, the officials started t become concerned about the housing market bubble, which would be more than disastrous for the economy when it bursts. Therefore, since March 2016, the government have issued a wide range of orders to curb the overheated real-state sector from mortgage restrictions, increased down-payment requirements, bans on purchases by non-residents (those without hukou) to directly limiting the number of homes that people can buy. “Houses are for living in, not for speculations (房子是用来住的,不是炒的)” this order from President Xi Jingping was emphasized again and again, and was quoted directly in the 19th People’s Congress report in 2017.

People started to feel uncomfortable. Sure, the official verdicts all sounded reasonable, but for those who have tied their entire family wealth into the housing market, the idea of top-down price curbs was a slap on the face.

While worrying about the collapses of house price, the Chinese house owners are now faced with another round of harvesting: property tax.

Noise around property tax had been buzzing on the background for quite a few years. After years of delay and opposition from vested interests, it looks like it is finally happening. Although government announcement is not yet out, since this March, various official news channels have all hinted, directly and indirectly, on the arrival of property tax in the near future.

As much as the government continues to emphasize that tax levitation is for curbing speculations, the common people - the ones who have spent it all for their houses, no longer buy the rhetoric anymore. In a country where land is still publicly owned, property buyers only get use-rights for their residential land for 70 years. If no ownership, why tax?

Shadowed by the trade war and domestic economic slowdown, this year, the Chinese people began to see, slowly but clearly, the insolvent reality:

China’s real estate market is not a fairyland filled with gold digs. On the contrary, it is a field filled with fertile chives. When the government is short of money, it is time for the people, the chives, to pay the price.

-

Chives Field No. 4: The (No Longer) Populous China

On August 6th, People’s Daily posted a commentary titled “Having kids is not only a family thing, but a national thing too”. In 1,000 words, it warned on the hazardous impact of the declining birth rate, and urged policy-makers, from national to local, to come up with more comprehensive welfare plans for young, fertile couples. “In the face of great economic pressure, people have no choice but to passively resist having kids,” wrote People’s Daily, “the government must take more targeted measures to solve the problem and provide a better life for its people.”

The piece might be intended to deliver message to bureaucrats and policy-makers, yet the public went furious simply by the title itself: for many people - the two of us included - it read as a calling for citizens to reproduce for the country. As a generation grew up influenced by individualistic values and used to single-child family structure, such idea was not only unacceptable, but also ridiculous to its core: we are a generation that can’t even afford our own livings, now you want us to have kids?!

Then things went worse.

Last week, Xinhua Daily, a provincial newspaper, posted a commentary in proposal of a “single tax” and a “maternity fund”. Written by two Chinese professors, it suggested those citizens with less than two children to contribute a share of their income into a public fund, which could only be withdrew when the individual has a second child or retired.

"What the heck is maternity fund? Are us chives destined to be harvested?"

Like oil spilled on fire, the article triggered public outrage at an unprecedented scale. Although the proposal was later criticized by CCTV, many believed it was intended for the government to testing out the water. Yes, there’s still a long way for a suggested proposal turning into state legislations, but the fact that such commentary showed up on party-owned media proved that policy-makers were at least thinking along this line, which, for angry netizens like us, were totally offensive.

Some of the comments from angry netizens questioning the government's changing birth policy.

In 2017, a year since two-child policy was issued, birth rate in China still dropped by 3.5 percent with only over 17 million newborns. Meanwhile, China’s elderly population is expected to reach 400 million by the end of 2035. We totally get the obvious problems here: the labor poor is draining out soon, and an aging population is putting significant strain on the national health and social care system. What we don’t get, and cannot stop feeling depressed about however, is the dire fact that the government is asking its people to pay for its own policy mistakes. The one-child policy messed up the national demography, caused endless cases of personal sufferings (remember all those forced abortions?) and institutional corruptions, now, when the policy’s negative impacts are surfacing out, the big guys suddenly changed idea and are now calling for second, or even more children from the people.

Who are we really, other than chives that are destinated to reproduce the next generation of, well, younger chives?

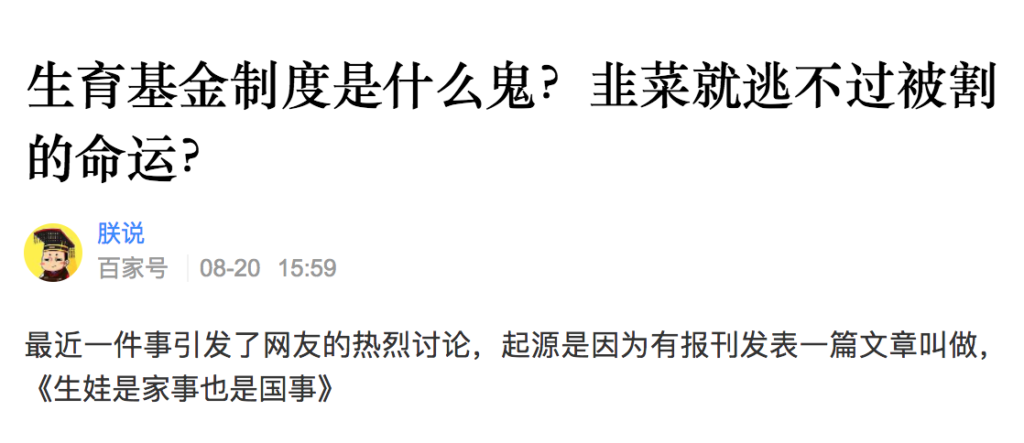

Left: slogan during the one-child policy period, "in order to get rich, we must plant more trees and have less kids".

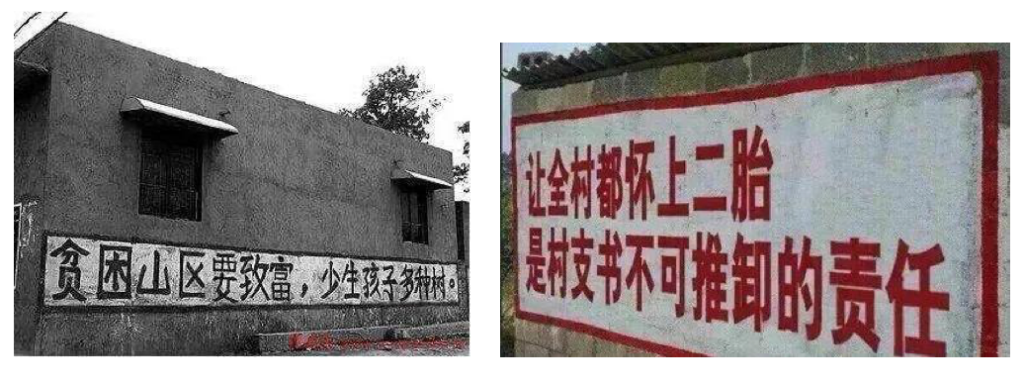

Right: slogan after the government opened second-child in 2016, "it is the party secretary's responsibility to make sure every family in our village has a second child. "

Half way through writing this article, we noticed that the term “chives state 韭州” is already being censored. “I bet chives is the next keyword to vanish from the Chinese internet!” A friend posted on her WeChat today.

It is indeed more than possible. Online and offline, we are seeing, and hearing everyday of people referring themselves as chives. Under such a common identity, the Chinese population is united, and are feeling for each other. Now that pink bubble of “economic miracle” is busted, we can no longer hide behind that Amazing China narrative that helped us to gain so much utopian faith on the political regime for quite some years. Instead, we are now all bare and clean, standing together, filled with equal vulnerability.

From reflections from other’s eyes, we are finally able to see who we really are. We are chives, green and exuberant, decorated by delicate white flowers; we are chives, growing endlessly and vigorously, never fear of any tough climate. We are the harvesters’ favorite, and we are always here, when our country needs us.

Yes, but I find the smell of chives strong and unpleasant.

Very perceptive analysis of the chive meme. Applause!

[…] Curious how that reference came about? Here is a great explanation from the writers at the Elephant-Room: […]

Where have I heard all this before? Why, in the US, after 1980, of course!

We ourselves could no longer rely on the “economic miracle” of the postwar period. And instead become chives ourselves – stores of money, savings and prosperity to be harvested by the Big Boys.

The US and China are converging to the same place – just from different directions. That place is paternalistic oligarchy.

And our value to those oligarchs – be they “capitalists” or the CPC – is in our harvesting.

Tx so much for posting this.

I’ll have to thank you for the success today

[…] schedules; others replace the underlying metaphor with a different kind of renewable resource: “chives.” Originally used in reference to hapless individual investors who repeatedly lost their shirts […]