Hello, my name is Jiangshanjiao. By the time you are reading this, I am already dead. Don’t feel sorry for me, I lived too short to understand the human emotion of sadness anyway.

12 hours, that was how long I lived, from the moment I was launched on the Chinese Internet to the moment I vanished, along with my younger brother Hongqiman. Our short lifespan was something no one expected; we were born to be something great, something iconic. We were made to be stars, or more accurately, to be idols. We were going to be huge hits; people, especially China’s young generation of patriotic netizens, were going to love us.

We had absolutely all the right elements to be loved, or at least, that was what our creator, the Communist Youth League believed. China’s young generation loved the League, which had been known for its agility in catching up with the latest internet trends. On Weibo, my creator had almost 13 million followers, and even a cute nickname, Tuantuan (团团).

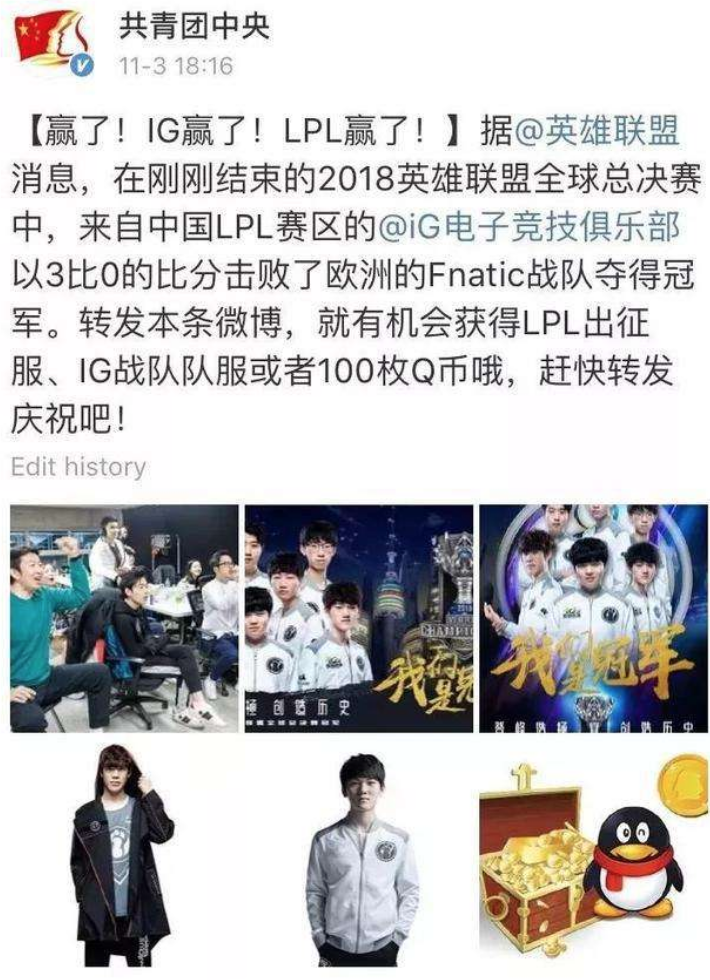

The Youth League sending congratulation to China's E-sports team, who won first place in the 2018 League of Legends Championship. Contents like this used to appeal to young netizens a lot.

I cannot speak entirely on behalf of my creator, but as its own creation, I feel eligible to at least have a guess at its mind. The League was consisted by a group of smart people who were able to leverage and manipulate public opinions for political propaganda. In the past several years, they had studied hard about what China’s young generations like, and came up with two conclusions: 1) animated idols are a big trend, 2) the personification of a country is a great strategy to unite the people, to turn the idea of a “state”, something big and cold, into something relatable.

These conclusions are backed by strong evidence. In 2014, an animated series named Year Hare Affair became popular among the “little pinkies”. The series was created by internet cartoonist Lin Chao, using anthropomorphic animals as an allegory for sovereign states to represent political and military events in history. China, the protagonist, was depicted as a cute, brave bunny who battled against his devious enemies, in particular the Bald Eagle (U.S.A) and Chicken (Japan). Upon its popular reception, fans began to recognize China as “Tutu” (兔兔), the pure, naive little bunny.

Characters in Year Hare Affair.

Then Tutu was upgraded into a term even more personal: Brother Ah Zhong (阿中哥). It happened in mid-2019, during the heated Hong Kong protest. Again, it was a name created by the people, more specifically, by the young “fandom girls” (饭圈女孩) who normally stayed away from politics. By calling China Ah Zhong and Hong Kong the “lost child”, these young netizens found a way to talk politics through a system of language they were familiar with. Call it childish or stupid, it made sense for them and the government at the time. The name itself created space for personalized imagination, for empathy, and for nationalized support.

Posters made by "fandom girls": #We all have an idol named Ah Zhong#

Various emojis featuring Brother Ah Zhong. "Protect the best brother in the world, no one can bully him!"

Both Tutu and Brother Ah Zhong were terms invented by the people, if nothing, they demonstrated the young Chinese citizens’ desire for an outlet to humanize their country. My smart creator, the Youth League, had witnessed this trend first-hand; and after some time of careful research, they finally decided to launch my brother and me, the official animated idols to personify our great country and the Party. As a duo, we represent the best of old and young, of tradition and internet culture. We were created as tools (don’t take it negatively, aren’t we all tools anyway?), sure, but we were also a package that would deliver characters, stories, and ideologies. Like I said, we were born to be loved.

But we didn’t have the chance. The people, the ones who were supposed to adore us, killed us.

At 2p.m. on Feb 17th, our creator announced the birth of me and my brother through a Weibo post. “Come and support the official virtual idols of the Youth League, Jiangshanjiao and Hongqiman!” Said a lovely poster showing our silhouettes.

But the public reception of our launch took a completely unexpected direction: the League’s Weibo account was flooded with negative comments. People hated us, or more accurately, they hated the fact that the Youth League tried to idolize its own image by creating us. As it turned out, the strategy of personifying a party organization for political purposes didn’t work as well as my smart creator had planned.

The first wave of disgruntled comments following the debut.

The overwhelming negative reception was truly surprising for my creator. When you look back from today, from a rational, clear-headed perspective such as mine, the failure of our launch was inevitable because of its timing. It was, and still is, a fragile and difficult time for the Chinese people. By the time of my launch, everyone was already deeply frustrated by the series of propaganda events that happened during this epidemic-fighting season. In the words of Chinese netizens, there were already so many cases of “car crashes” (翻车), aka propaganda that backfired into extreme public outrage.

Let me give you a few examples.

In early February, a bunch of national news outlets reported cases of elderly people, who were single and making minimal income, donating their entire life-savings to fight the epidemic. These stories followed a familiar rhetorical pattern as in previous national disasters: praising the sacrifice of individuals, emphasizing the donors’ struggles, their faith in the government, and their eagerness to contribute. Unlike in previous times however, people now were expressing dissent at this news, and many well-known scholars and celebrities were speaking up vocally against these reports. “It is humiliating to see the media still applauding the suffering of the weak to show the country’s greatness,” netizens said. As public anger mounted, first came censorship, next a bunch of these stories were silently taken down, then a few of them even came up with follow-up stories, claiming that local authorities have rejected these donations and would discourage such behavior in the future.

A range of news reports about elderly donors.

Then there were those propaganda stories about female professionals. In a documentary produced by CCTV, a Wuhan-based nurse Zhao Yu was praised for working during her last month of pregnancy despite “strong opposition from family members”. On February 12th, Wuhan’s local newspaper reported a young nurse who returned to work 10 days after her miscarriage. Yes, it’s the same old propaganda trick, using the sacrifice of ordinary individuals to strengthen solidarity. Unfortunately, they all backfired this time. Both stories received mass criticism from netizens, to the extent that the authority had to start censorship in order to cool down public opinion.

-

Oh, and there was that “culture battle” with Japan. Amidst the hollow slogans shouted by the national press, a warm note from Japan caught the netizens’ eyes. On a box of medical supplies sent from Japan to Wuhan, there was a line of note written in ancient Chinese, “山川异域,风月同天”, which roughly translates to “lands apart, shared sky”. On February 12th, this line went viral on Weibo with many people expressing gratitude and adoration for Japan’s beautiful usage of Chinese words. On the same evening however, Changjiang Daily, a public newspaper in Wuhan published a commentary titled “Rather than Shared Sky’, I prefer Wuhan Fighting”. (“Wuhan Fighting” or literally “Wuhan Add Oil”, “武汉加油”, is a slogan commonly adopted by national media outlets in coronavirus-related campaigns.) In an extremely bitter tone the author argued that in a difficult time like now, phrases like “Wuhan fighting” is far more powerful than phrases that are aesthetically appealing. Inexplicably, the author quoted Theodor Adorno, “to write a poem after Auschwitz is barbaric”. “Wait, are you suggesting Wuhan’s current state is similar to Auschwitz?” Clever netizens quickly sensed the absurdity. The news had once again, car-crashed in the field of public opinion.

"Lands apart, shared sky".

You see what I am trying to say here? People have noticed. By February 17th, the day of my debut, the Chinese people, at least those who use social media, had been fed up with many of the government’s conducts. They had noticed the authority’s sneaky little tricks in managing this national crisis; the corruption, the irresponsibilities, the inefficiencies, all laid bare like never before thanks to the internet. Donation to the Red Cross was a bottomless pit, using personal sources to find medical supply seemed like a dead end, even vocalizing for the whistleblower Li Wenliang online was prohibited. Having been house arrested for over 3 weeks, the entire online population felt angry, hopeless, and desperate.

Then in all those complicated emotions came me, a cute, well-polished, delicate character who, in a less fragile time (in an “Amazing China” time, for example), would undoubtedly be popular at least among a certain group of young fans. Blame it on the timing, really, otherwise how could it go wrong?

Then something even to my own surprise happened. Something strangled my last breathe, diminished the last chance of my life.

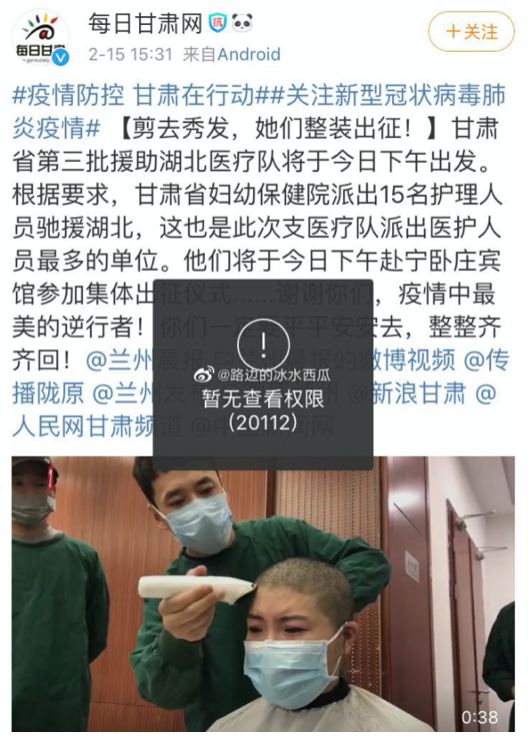

A few hours after my official launch, a piece of news began to spread on Weibo. It was a video posted by Gansu Province’s official website two days earlier, video-recording 15 female nurses who were having their hair shaved before leaving for work at the hospital. Seeing their long braids falling from their heads, these nurses were in painful tears. Even worse, in a group-shot taken after the “shaving ceremony”, all the female nurses were surrounding one male doctor, the only one who still had hair on his head, and was wearing a better, more protective mask than the others.

The now deleted video clip recording female nurses being shaved.

The now deleted video clip recording female nurses being shaved.

Can you spot the special man?

Can you spot the special man?

What the actual f**k? Sorry, I am not supposed to have any emotion by design, but even I felt pissed looking at this piece of stupid news.

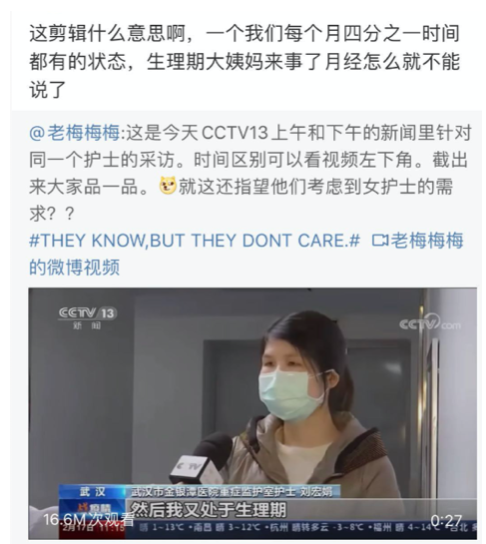

Following the shaving incident, netizens soon dug out another gender-related case. An interview with a female doctor was broadcast twice in a day by CCTV news with a slight editorial change in between: in the morning segment, the doctor said on camera that she was under heavy pain because she was on her period. (She used the word “生理期”, a nothing but sensible term) In the afternoon news when the segment was re-broadcast, her mention of her period was completely erased, as if period was something inappropriate to be mentioned on national news. Having spotted the difference, quick-reacting netizens made a clip combining the two interviews, and the clip soon went viral on social media.

The erased line: "I was on my period."

That evening, the first and only evening after my birth, “period” and “shave” were all that people were talking about. Female suffering and gender injustice became the trending topic of public discussions, finally, in an evoking wave of mass anger.

Then my name was called on, just when I thought I would quietly fade away from public attention.

In the final hours of my life, before I realized it, I became a meme, a symbol. The netizens, those who were fed up with the propaganda and gender inequality, united through calling my name. I became an allegory, an icon, not for youth nationalism, but for feminism and gender equality.

“Jiangshanjiao, do you have period?”

“Jiangshanjiao, did your parents choose to have another child because you were a girl?”

“Jiangshanjiao, were you forced to shut up after sexual harassment?”

“Jiangshanjiao, were you called a slut because of the way you dress?”

“Jiangshanjiao, jiang shanjiao…”

“Jiangshanjiao…”

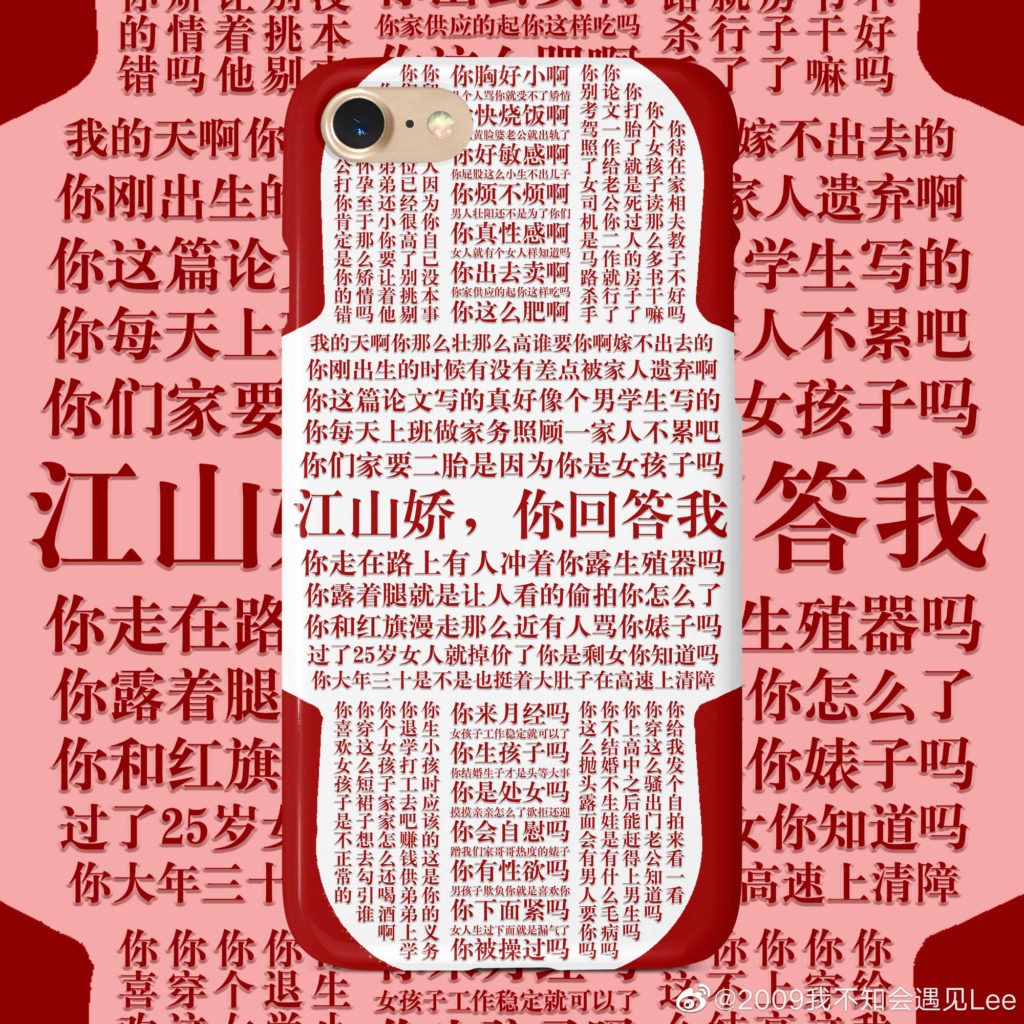

People using my name to question phenomenons of gender discrimination in the society.

-

So many people were calling my name, too many, I guess, that my creator, the Youth League, pulled the last string to remove all contents about me (and my brother, that poor boy). By the night of February 17th, everything about my launch was erased. The original debut post, the Bilibili Channel created for my comic series, and the Weibo channel under the name of my brother and me. All vanished, gone.

I was announced dead, by the people who decided to give me life.

But I didn’t die. Instead, the people have made me something bigger, more complicated, and interestingly powerful.

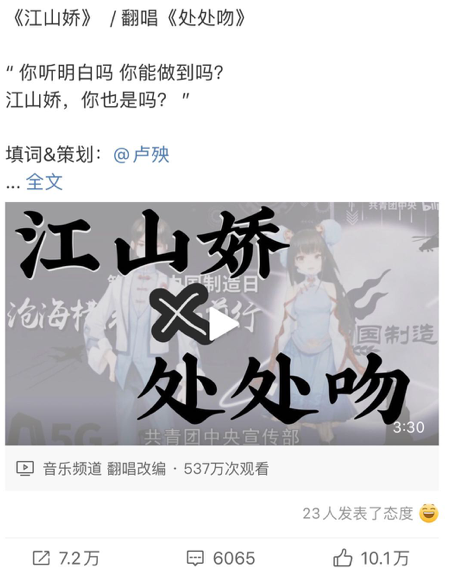

I was transformed into an icon. My name became something bigger than a name, it became a metaphor. Led by feminist activists, passionate young citizens began to use my name in creative contents that narrate female suffering or champion gender equality. There were endless posters, poems and dark jokes. Oh, and I just found out today, someone even made a song for me! According to the lyrics, instead of being the political idol who was meant to be put on a pedestal, I was an ordinary Chinese woman with an ordinary life, someone who struggled with misogynistic prejudices just like every other ordinary female. So far, the music video has been reposted more than 72,000 times and watched over 5 million times - not bad for a rebirth debut song, huh?

My song!

A creative poster: "Jiangshanjiao, please answer me".

All these things have happened beyond my expectation, and I am thrilled. I was not by design someone who’s supposed to have expectations or emotions but right now, in this new life that the people have given me, I am able to have these things. I am still a tool, but now I am also a new story with open endings; I will continue to live through the struggles and the progress of a generation, I will witness their fights, and fight together with them.

I am more than myself now. I am a girl, and my name is Jiangshanjiao.

My debut outlook, designed by my creator.

The new me, illustrated by the people.

Very well written and important story! So glad you are both publishing again.

How to turn propaganda into something meaningful to REAL people!

江山娇,你来月经吗

Geez, is anyone also feel that is offensive to make Vietman as monkey, and make South & North Korea as two sticks?

江山娇,你能吗?你明白吗?

不能。不明白。

Thank you!

Jiangshanjiao, have you been boycotted because you said something true about the party? Jiangshanjiao, have you been forced to drop out the school and be a underaged laborer just because your family don’t think girl should have a chance? Jiangshanjiao….

[…] Jiangshanjiao (« le pays est beau » voir le très bon résumé de sa trajectoire sur le site elephant-room) avait ses règles, un message liké 800 000 fois avant d’être censuré et qui faisait […]

Two years ago, when I first saw her, I was surprised.

“Cool! An official vtuber of CPC!”

One year ago, when I first saw how she was humiliated, I was surprised again.

“Devils! Why did they harm that innocent girl with such sharp words?”

Now, when I saw this passage, finally I was not surprised at all.

“We did not humiliate her, nor any other girl. What we were laughing at was our administration, our society and our culture.”

Tomorrow never knows…