When Sponsors Become Daddies (金主爸爸) : a Look Into China’s Entertainment Industry

If there’s one Chinese reality show that we have poured true emotions into this year, it would be Sisters Who Made Waves (乘风破浪的姐姐).

We were absolutely fascinated when we first learned about the concept of this show. Unlike other Chinese variety shows that were dominated by cute young boys and girls, Sisters features 30 female celebrities over 30 years old, many of them nationally-known actresses and singers with established careers, to compete for the opportunity to form a female band. Just thinking about the scene of 30 high-achieving, witty, beautiful, and mature Chinese women living and competing together on camera - how refreshing is that? (we were fantasizing a lot of diva dramas for sure!)

When Sisters debuted on Mango TV in mid-June, it felt like the whole country was paying attention. The show pulled a total of over 370 million views after the first episode aired, and discussions about it dominated every Chinese social media platform. Back then, Chinese audiences like us were thrilled that we’ve finally found a reality show that met all of our expectations: high-quality production, fun to watch, and more importantly, socially meaningful as the show touches a critical gender issue in today’s China: the female struggle to break through age and gender stereotypes in a highly competitive, patriarchal society.

We were seriously damned excited. So excited that I, someone who had never watched anything on Mango TV, downloaded its app and paid 25 RMB for a monthly membership. For Sisters this would be worthy I thought; I am not just paying for a TV show! I am paying for female empowerment and social progress!

30 Sisters making their debuts in the first episode.

As we are writing in mid-August, Sisters has aired 10 episodes, which means for 10 consecutive weeks we’ve spent almost three hours (yes, that’s how long Chinese reality TV episodes are) every week keeping up with the show. So far, half of the 30 contestants have been voted out by the viewing public after many rounds of nerve-wracking performances. Although the final result is still a mystery, many fans, including the two of us, are gradually losing interest. We are unlikely to ditch the show completely (still loving the contestants, our dear sisters!), but by this point we are officially annoyed by two particular things:

- The show’s failure to dive deep into the social problems about which it could potentially stir up discussions. This is a whole other topic and we will save those discussions for later.

- All. The. Freaking. Ads!!!

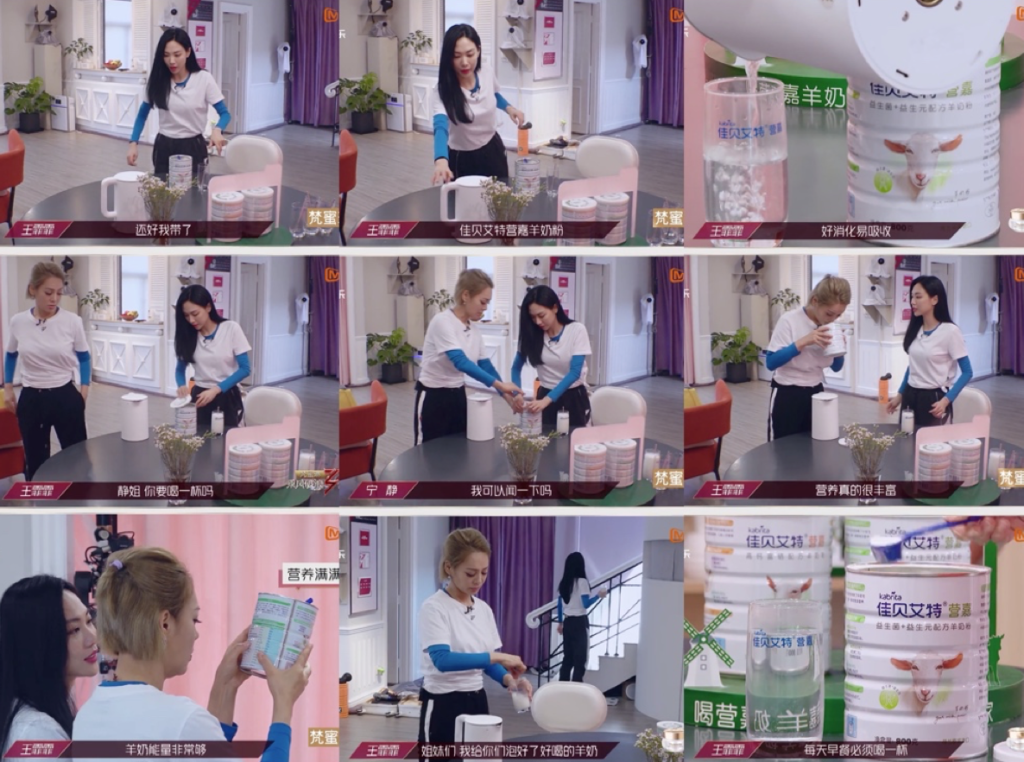

My 25 RMB membership fee, as it turns out, only earned me the pathetic privilege to skip those pre-rolled ads. The rest of the advertising, mainly in the form of direct product placements are still everywhere in the show. From milk powder, detergent, snacks, cosmetics, technology gadgets to plastic surgery app, for approximately every 20 minutes of content, there is a segment of the Sisters showing various products, raving about them in scripted acts like this:

This:

And this:

We know product placement has a long history of entanglement with the global entertainment industry and we totally understand it from a capitalistic point of view. The production of a massive reality show like Sisters is extremely costly hence sponsorship and brand endorsements are essential; and the contestants, our dear Sisters, they must be in desperate need of income source given Covid-19’s hit on the entertainment industry. But the more understanding we are the more we entrap ourselves in a moral paradox: on one hand, we don’t mind, and sometimes even support the capitalists and celebrities making money, but on the other hand, excuse me! I paid my 25 RMB and now you give me this??

Since when have we become so tolerant of the ubiquitous product placement in Chinese entertainment?

The Rise of Sugar Daddies (“金主爸爸”)

In today’s China, everyone would use a term to describe clients in the entertainment industry and all the other business: “金主爸爸” (Sugar Daddies). Sometimes people would even refer to their clients simply as “爸爸” (Daddies), setting up a submissive power dynamic between two parties like never before.

It all started in 2014, thanks to a specific variety show and one guy.

6 years ago, when online variety shows became immensely popular in China, production teams were struggling to break through the traditional advertisement model that often seemed abrupt and ineffective. Ma Dong, the former content director of iQiyi and now the CEO of a leading entertainment production company in China, first came up with his “fancy verbal endorsements” (花式口播) for sponsors - who Ma called his Daddies - in the debate show You Can You Bibi (奇葩说). Being an experienced talk show host, Ma managed to sneak in the sponsors and their slogans into his show in a humorous, self-mocking way. As You Can You Bibi rose in popularity online, Ma’s verbal endorsement itself became a highlight of the show. His blunt expression of gratitude towards his “daddies” was not only well-received by audiences, but also pricked the bubble of the entire industry: it is because of the sponsors that we get to see these wonderful entertainment productions nowadays.

The Daddies were acting in grace, and we must count our blessings.

When Ma called out the brand sponsors, the screen popped up with a sticker labeled “Time to Make Money!”

Season 2 of U Can U Bibi, in 2015, became the first online variety show in China that made over a million RMB worth of advertising sales. All of a sudden, the marketing geniuses were awakened, and all the production teams broke the leash on their way of pleasing the sponsors. If the audiences didn’t mind Ma’s funny call out to “daddies”, it surely means there’s space to fit more ads and product placements into other domestic entertainment productions. After all, we all know who the boss is now.

From the variety show The Big Band, currently airing on Iqiyi.

Platforms in Dilemma

In China, there are today four major video-streaming platforms that offer PGC content: iQiyi (invested by Baidu), Tencent Video, Youku (invested by Alibaba) and Mango TV (a constituent company of Hunan Province’ public television network). All the popular entertainment productions in recent years, mainly TV shows and reality variety shows, have been co-produced by one of these platforms with other private companies like Ma’s.

In 2015, iQiyi first began to explore the possibility of paid membership by charging about 20 RMB a month. Thanks to a number of top-rated TV shows it co-produced back then, the platform managed to gain a meteoric rise of membership in the first several years. In 2019, it announced that its paid members population broke through 100 million. By then, all the other platforms had also launched their own membership programs at a similar price point.

But this was far from enough in terms of sustaining the business. Paying for digital content was, and still is a new concept in China, and users were not accustomed to paying subscription for entertainment shows even at a much lower price comparing to western platforms such as Netflix. Pressured by investors, platforms which were struggling to become profitable came up with “super memberships” and other extra paid-services which quickly flopped in terms of public reception. In December 2019, iQiyi and Tencent video launched their “super-advanced streaming” service for the hit show 庆余年 (Joy of Life, a fantasy drama), on top of the paid subscription, the services offered “advanced access” at the cost of 3 RMB per episodes for those who wanted to watch the most recent episodes. Such service received a massive backlash from its paid members, some even sued the platforms in the courts calling for compensation.

Poster in promoting the "advanced access" program.

So here is where all the Chinese video platforms are standing today: after years of burning cash for content production and attracting new viewers, the income from paid memberships is still far from enough to cover the costs. Pressured by capitals, they are left with no choice but to turn to advertising sales at the expense of user experience. Reality shows thus became a fertile land for product placements and brand endorsements; one minute two celebrities were having a heart-to-heart chitchat about personal lives, the next minute one would offer goat milk to the other, praising its nutritional value and good taste. TV shows are not exempted either; reality-related television series would be filled with brand-related plots, often with the characters sedulously mentioning certain brands in order to bury it seamlessly into dialogues.

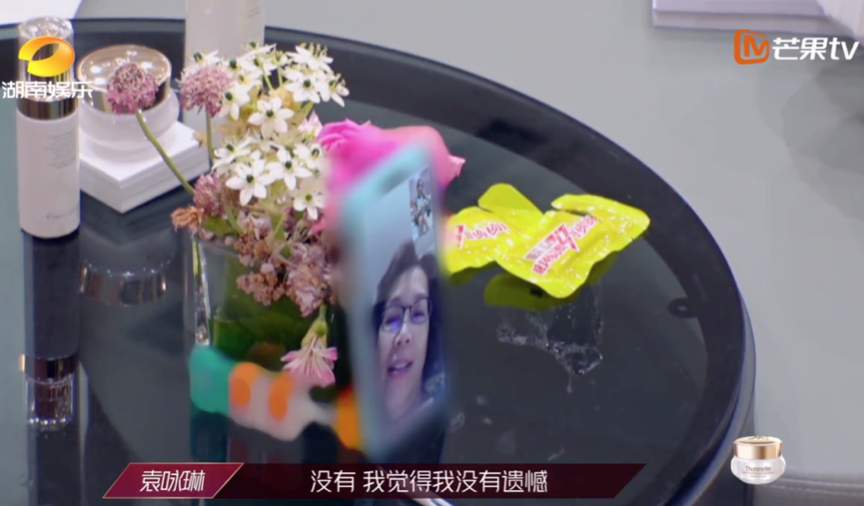

Some of the countless product placements in this year’s hit TV Show 三十而已(Nothing But Thirty).

What used to be quality first has now officially become profitability first. As a friend who works in Tencent Video told us earlier this year, their logic of producing a show has changed from assessing its quality to assessing its business potential. Today, platforms would no longer give green light for a production unless the marketing team has already found sponsors to cover the production cost.

We get it, dear platforms, you guys are struggling, you must work hard. We like the shows you produce so we won’t complain, but we, your consumers, have a baseline too. At the end of the day, don’t we have the right to just complain a little?

We do have such a twisted love-hate relationship with our Chinese platforms.

With the economy stagnating, it is getting harder for shows to find a single-title sponsorship to cover the entire production cost. Instead, we are witnessing an explosion of co-sponsors, sometimes up to a dozen of them, putting brand logos and product placements every few minutes on the screen.

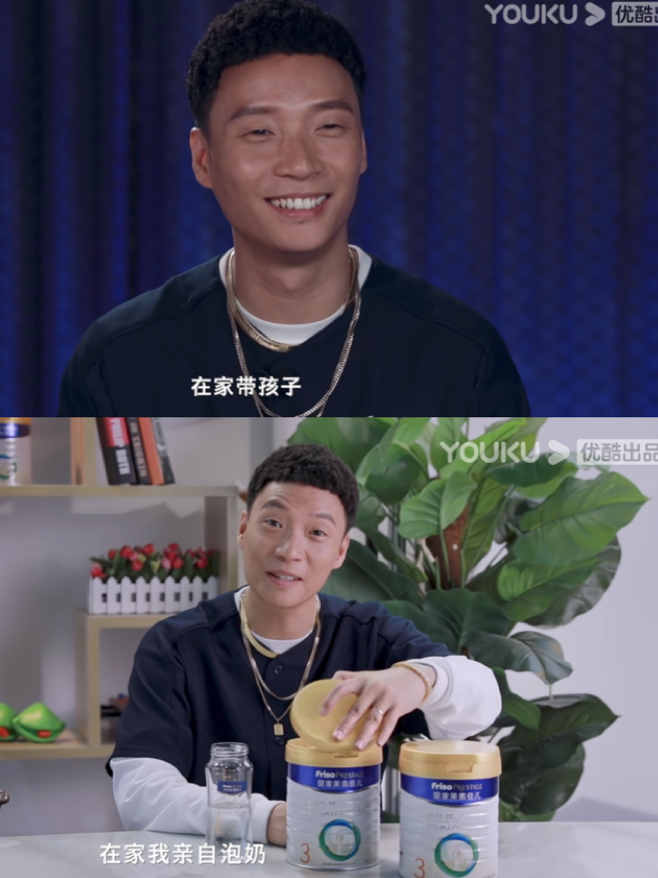

As Vivo is a sponsor of Sisters, all the scenes of celebrities using other phones were blurred, even when a candidate was having a sentimental face-timing moment with her mother.

One day last week, I was watching season 3 of Street Dance of China, a pioneering variety competition that gathers top street dancers across the country. Half way into the show, the camera turned into a dancer telling the audience about his busy life of taking care of his recently born second-child. I was assuming that this was part of his personal interview speaking about the struggle of being an underground dancer and a father but the screen suddenly turned to him opening a can of formula milk and broadcasting the slogan of the sponsoring brand. “Thanks to this formula milk, being a dad of a new-born is no longer such a hassle!” He says cheerfully. Watching him stirring his milk, I felt at the same time bitter and sweet, happy for the extra income he’s earning and sad for this entire scenario.

When I mentioned this to a friend over lunch yesterday, he was surprised at my reaction. “What’s the big deal here?” He raised his eyebrows, “this is the norm nowadays and everyone is happy with the outcome, why so surprised?” “But I am a paid-consumer! Don’t I deserve purer content of some sorts?” “Well, you always have the option to press fast-forward, don’t you? No one is stopping you from not watching these ads.”

I was quiet. In many ways he is right: the ad scenes are there, but I do have the right to skip them with a few button-presses. But in other ways I still feel unsettled, as a consumer and as someone who enjoys domestic entertainment and who hopes the industry can continue to grow, I have to ask how sustainable this current model really is, when capitalistic gain has replaced content quality to become the goal of an entire industry.

Perhaps we are driven by a positive engine or perhaps we are free falling but we don’t know.

so lucky the period dramas are

As a Taiwanese I turned to your site for more information of China. This is just weird. I like your words, truly genuine.